Europe’s new ‘Eastern bloc’

Beijing’s diplomatic masterstroke has put former Soviet countries on a collision course with Brussels.

By MARTIN HALA

PRAGUE — For Central and Eastern European countries, accession to the European Union has driven democratic reform and economic development. But after financial and refugee crises left the bloc reeling, the link between liberal democracy and social well-being is not as evident as it once was. As narratives of a decadent, failing West take hold, the rising East looks increasingly attractive.

And China is taking full advantage.

Free from the shackles of Soviet power, Europe’s eastern countries have voluntarily joined a new grouping that again divides Europe into East and West — this time under Chinese tutelage. “Eastern Europe 2.0” is a much softer arrangement than the old bloc. But it poses a serious threat to the region’s security and prosperity by undermining existing alliances and ushering in a return to oligarchic tendencies following the “China model.”

The grouping — formalized in April 2012 as the “16+1” initiative — brings together the People’s Republic of China and 16 post-communist Central and Eastern European countries. It has received little attention in the West. But, more worryingly perhaps, is that its implications are hardly understood in the region itself.

Tilted scales

In Beijing, 16+1 was until recently considered a masterstroke of Chinese diplomacy. Not only did it divide Europe, but it herded together countries from Russia’s former backyard and the EU club without much protest from either.

Ironically, it’s precisely the incompatibility with EU practices that heightens the appeal of China’s initiatives among some Central European elites

The EU is preoccupied with other problems, from migration to Brexit. And Russia’s tacit consent is the sign of a growing tactical cooperation between the two powers first practiced in Central Asia through the Shanghai Cooperative Organization.

Initially, the very vagueness of the 16+1 project may have helped China to pull off its surprising feat. The project’s early documents are full of lofty terms such as “win-win,” “friendship” and “harmony” and stress compatibility with the “China-EU comprehensive strategic partnership.” It’s likely that at least some Central and Eastern European leaders did not fully understand what they were getting into.

More recently, the 16+1 initiative has effectively become the East European platform for the implementation of Chinese President Xi Jinping’s grandiose Belt and Road Initiative, the paramount focus of China’s foreign policy. Perhaps because of this redundancy, and the rising unease in Brussels, China has recently decided to step on the brake: Future 16+1 summits are to be held once every two years, instead of the current yearly format.

China still has an overwhelming advantage in the arrangement. The 16+1 scheme does not allow its members to function as a regional bloc in dealing with China — rather, it organizes 16 bilateral relationships into a convenient format for Beijing.

China’s footprint is clear: the politicization of the economy

Bilateral parternships make it easier for Beijing to bypass existing alliances and realign countries as part of a new China-centric system. The 16+1 grouping cuts across EU boundaries — it includes 11 EU members and five non-members — and offers Beijing an alternative to dealing with the EU as a whole. Instead of bargaining collectively, 16+1 countries end up competing to become China’s favored “gateway to Europe.”

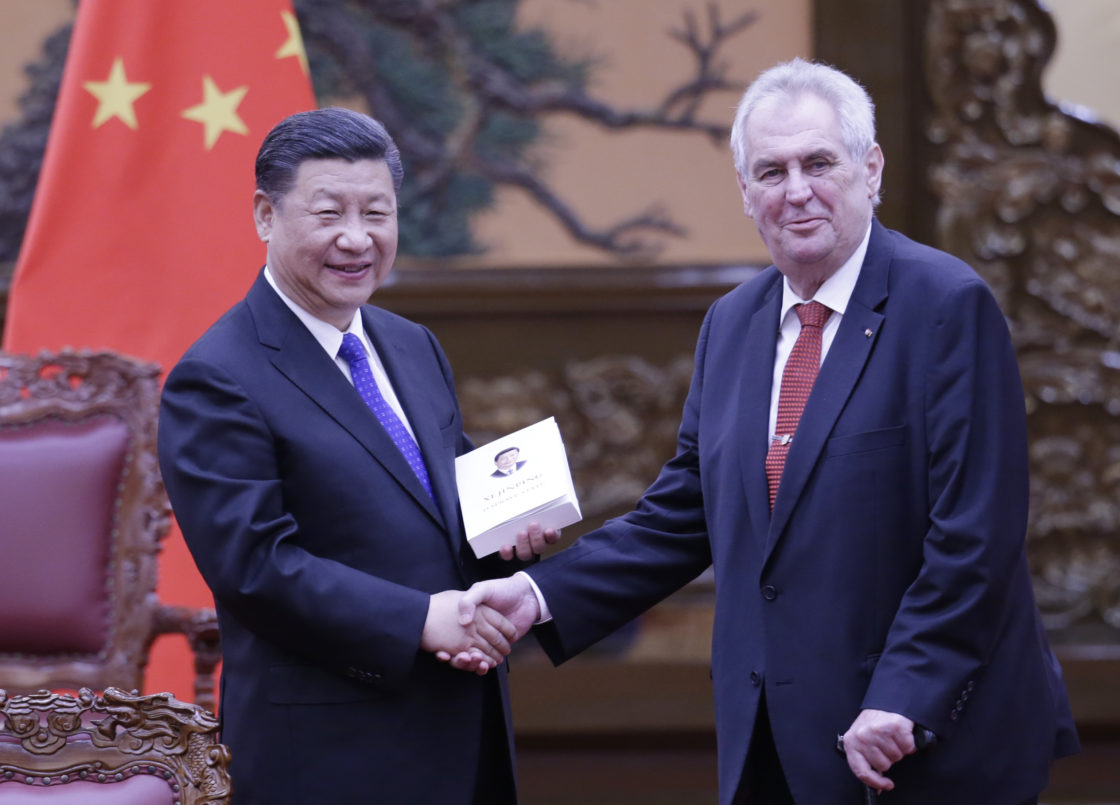

In the ensuing race to the bottom, Czech President Miloš Zeman has publicly offered his country as an “unsinkable aircraft carrier for China in Europe,” and Serbian politicians have mused about standing out as the best student in China’s class in a way that would transform the “16+1” into a “15+1+1.”

Such competition is partly a function of the 16+1 structure: The secretariat and administrative staff are based in China’s foreign ministry, reducing European countries to passive recipients of policies developed in Beijing.

The setup has also emboldened some countries to symbolically distance themselves from their existing alliances. In an interview preceding Xi’s 2016 visit to Prague, Zeman declared that the Czech Republic — a NATO and EU member — had previously been “too submissive” to Brussels and Washington and cast the new partnership with China as a sign his country was becoming fully independent again.

Former Serbian President Tomislav Nikolić took a similar tack last year when he declared Serbia — which officially aspires to join the EU at the earliest opportunity — is a free country and therefore not afraid to forge a partnership with China.

‘China model’

The idea behind 16+1 was for Europe’s eastern countries to tap into China’s economic potential, mostly by attracting investment. But the overall level of Chinese investment in the region remains low in comparison both with other players’ investment and with China’s investment in Western Europe.

It’s hard to measure the real political impact of this grouping, given it has produced few truly informative publicly available documents. In the Czech Republic, for example, an initial PR blitz has given way to a closed-door approach with journalists excluded from most bilateral events and top-level visits kept quiet.

But in one respect, China’s footprint is clear: the politicization of the economy.

Chinese diplomacy is pursuing “Globalization 2.0” — essentially the exportation of the “China model” of state capitalism, which combines select market mechanisms with overall control by the party state.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative and 16+1 are both political projects aimed at shaping the economy — and by extension the politics — of participating countries. In most, these frameworks create enclaves that operate according to Beijing’s “model” of political deal-making. This means Chinese politicians and businessmen can conclude deals with local counterparts that allow them to sidestep the usual transparency and accountability mechanisms.

The “China model” is colliding with that of the EU. While the latter is based on regulation designed to ensure fair and open competition, the China model spurns regulation in favor of ad hoc negotiation — preferably at the bilateral political level behind closed doors.

One example is the upgraded Belgrade-Budapest rail link, part of the Land-Sea Express Route designed to connect the Greek port of Piraeus — bought in 2016 by China’s Cosco Pacific — with Hungary. Shortly after the final agreements were signed in late 2016, the European Commission initiated an inquiry into a suspected breach by Hungary of EU rules mandating public tenders.

Flouting EU rules has admittedly become something of a national sport under Viktor Orbán, but the Hungarian prime minister is not the only one ready to bend the rules where China is involved. In the Czech Republic, China reportedly demanded that it be assigned a contract without a public tender for new construction at the nuclear power plant in Dukovany.

Ironically, it’s precisely the incompatibility with EU practices that heightens the appeal of China’s initiatives among some Central European elites. The bloc’s funds come with strong transparency and accountability requirements, while China’s money has “no strings attached.” This not only cuts down on paperwork, but also means that funds from Beijing can more readily feed into patronage networks.

Since the 1990s, when privatization carried out under slapdash regulatory frameworks gave the advantage to a well-connected few (often old-regime insiders), many economic elites in the region have gained control over key sectors through backroom deals and political connections rather than entrepreneurial prowess. These new oligarchs often find it easier to do business with their counterparts in China (and Russia), who share similar pedigrees and business practices, than to adapt to the strict EU regulatory regime.

Europe’s fringe countries have been set up for a major clash: between open-tender requirements and contracts awarded via political deals; between economic competition and the collusion of economic and political interests; and finally, between democratic capitalism and a state capitalism dominated by shadowy oligarch networks.

Despite all the talk of a win-win, Europe’s 16+1 members will have to make a choice.

Martin Hala is director of AcaMedia and of Sinopsis.cz, a website tracking topics related to China in the Czech Republic. He is co-editor of “Investigative Journalism in China: Eight Cases in Chinese Watchdog Journalism” (Hong Kong University Press, 2010). A version of this article will appear in Journal of Democracy’s April issue.